The Rothschild business houses are renowned for their integrity. In this Choice, we look back 200 years to correspondence between the extraordinary ‘Sir Gregor MacGregor’ and the London house of Rothschild, and the refusal by Nathan Mayer Rothschild to be taken in by what has been called one of the most brazen confidence tricks in history.

Gregor MacGregor (1786-1845) was a Scottish soldier, adventurer and confidence trickster who attempted from 1821 to 1837 to draw British and French investors and settlers to ‘Poyais’, a fictional Central American territory that he claimed to rule.

From respectable soldier to reckless colonial adventurer

MacGregor joined the British Army in April 1803, serving in the Peninsular War. He married Maria Bowater, the daughter of a Royal Navy admiral, around 1804. On his return to Britain, MacGregor and his wife settled in Edinburgh. There he assumed the title ‘Colonel’, wore the badge of a Portuguese knightly order and toured the city in an extravagant coach. Failing to attain high social status in Edinburgh, MacGregor moved to London in 1811 and began styling himself ‘Sir Gregor MacGregor, Bart.’, falsely claiming family ties with dukes and barons. MacGregor nevertheless created an air of respectability for himself in London society, but in December 1811, Maria MacGregor died and he lost his main source of income, and the support of her influential family.

MacGregor could not face the prospect of returning to his family farm in Scotland. His only real experience was military, and his interest was aroused by the colonial revolts against Spanish rule in Latin America, particularly Venezuela. The Venezuelan revolutionary General Francisco de Miranda had been feted in London during a recent visit, and MacGregor formed the idea that exotic adventures in the New World might earn him similar celebrity. He sold the small Scottish estate he had inherited and sailed for South America via Jamaica in early 1812. Arriving in Caracus a fortnight after much of the city had been destroyed by an earthquake, he introduced himself as ‘Sir Gregor’ and offered his services to the republican side in the Venezuelan War of Independence. As a former British Army officer, he was given command of a cavalry battalion with the rank of colonel and between 1812 and 1816, he fought against the Spanish on behalf of both Venezuela and its neighbour New Granada. MacGregor married Doña Josefa Antonia Andrea Aristeguieta y Lovera, daughter of a prominent Caracas family and a cousin of the revolutionary Simón Bolívar in June 1812. He captured Amelia Island in 1817 under a mandate from revolutionary agents to conquer Florida from the Spanish, and there proclaimed a short-lived ‘Republic of the Floridas’. He then oversaw two calamitous operations in New Granada during 1819 that each ended with his abandoning British volunteer troops under his command. MacGregor conferred invented decorations and titles on his officers, fraudulently obtained (and squandered) money and generally behaved abominably.

Poyais – ‘land of opportunity’

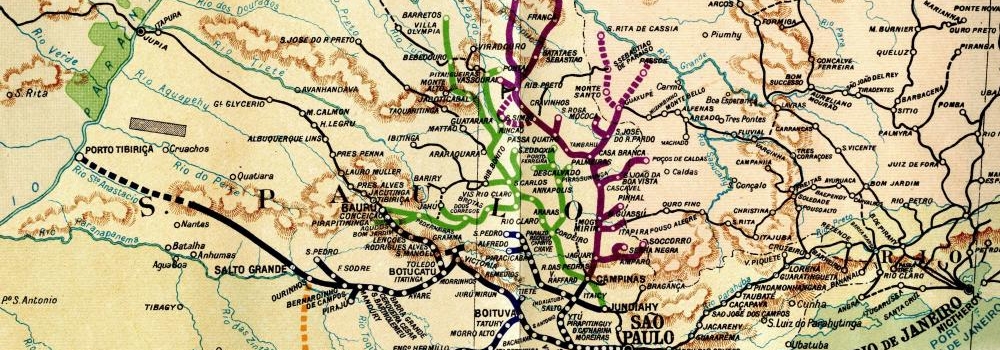

MacGregor arrived at the court of King George Frederic Augustus of the Mosquito Coast, at Cape Gracias a Dios on the Gulf of Honduras in April 1820, where George Frederic signed a document granting MacGregor and his heirs a substantial swathe of Mosquito territory - an area larger than Wales - in exchange for rum and jewellery. The land was pleasing to the eye but unfit for cultivation and could sustain little in the way of livestock. MacGregor named the territory ‘Poyais’ after the inhabitants of the highlands of the area.

In mid-1821, he appeared back in London calling himself the ‘Cazique’ (Native Chief) of Poyais, a land entirely of his own invention. London society remained largely unaware of MacGregor's failings, and in a climate where Latin America was distant, it did not seem so implausible that there might be a country called Poyais or that MacGregor might be its leader. His exotic appeal was enhanced by his wife, Josefa, the self-styled ‘Princess of Poyais’. The Cazique became an honoured guest at the dinner tables of sophisticated London, even attending an official reception at the Guildhall hosted by the Lord Mayor of London.

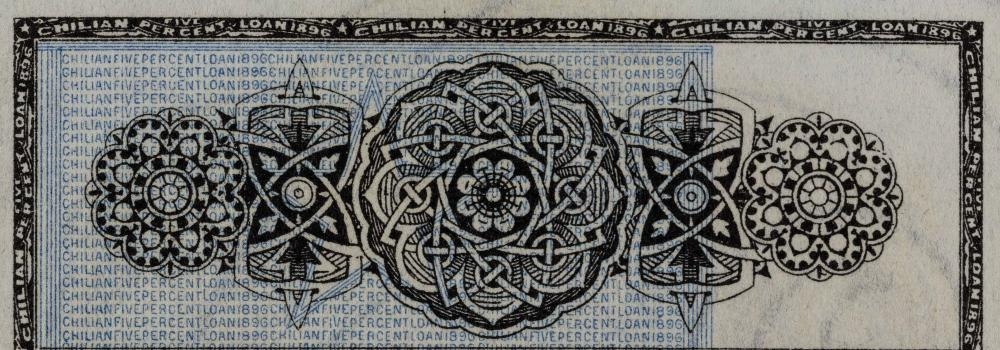

So began what has been called one of the most brazen confidence tricks in history - the Poyais scheme. MacGregor devised a parliament for Poyais and invented banking and commerce mechanisms. His imaginary country had an honours system, landed titles, a coat of arms and an army. MacGregor had ‘Poyaisian’ offices set up in London, Edinburgh and Glasgow to sell impressive-looking land certificates to the public. Following the Battle of Waterloo and the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the British government bond, the consol, offered rates of only 3% per annum on the London Stock Exchange. Those wanting a higher return were attracted by more risky foreign investments. MacGregor mounted an aggressive sales campaign, giving interviews in the national newspapers, engaging publicists to write advertisements and leaflets, and had Poyais ballads composed and sung on the streets of London, Edinburgh and Glasgow. His publicists described the fictional Poyaisian climate as "remarkably healthy” and “the soil was so fertile that a farmer could have three maize harvests a year, or grow cash crops such as sugar or tobacco without hardship”. MacGregor also orchestrated the issue of a Poyaisian government loan on the London Stock Exchange.

An audacious fraud

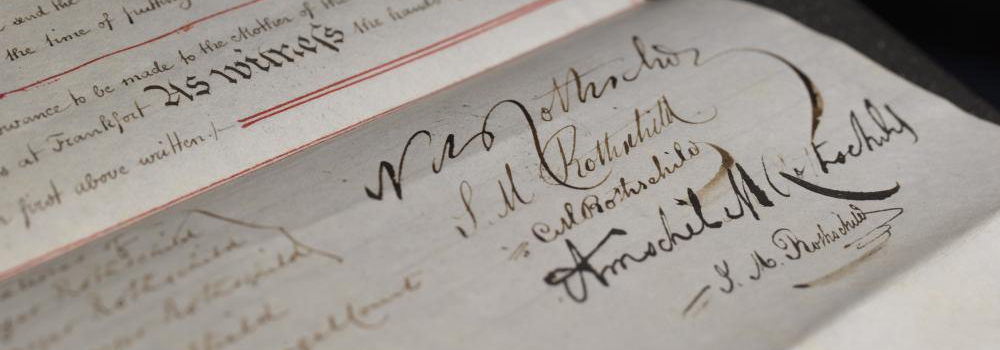

MacGregor contacted all of London’s foremost financiers in pursuit of profit. In June 1821, en route to England, he wrote to Nathan Mayer Rothschild, using the fraudster’s classic tricks of appealing to known interests of his target (soliciting support for a Jewish Poyais colony), whilst being deliberately vague about details.

“l have the honour to acquaint you that I arrived here with my family from South America, about three weeks ago; my letter book being on board of another vessel with my papers, I am unable to refer to the date of my letter to you from Santa Martha, enclosing the little deed for the grant of land upon the Zachosylyan river, in the territory of Poyais the proposed situation of the projected Hebrew Colony. I shall not at present enter into any details upon the subject, until I learn from yourself you approve of the plan. In the meantime I propose from procuring in Germany and Poland some twenty or thirty industrious agricultural Hebrew families to send out to Poyais, supplying them at the same time with provisions and everything else they may want for the first twelve months…It is proper to observe that the State of Poyais is disposed to remain perfectly neutral during the existing contest between Spain and her Colonies… I propose making the harbour of Port Royal … a free port which will immediately give it a considerable trade, as there is no port to leeward of Jamaica for reception of American produce….

‘Gregor MacGregor of Poyais’ to N. M. Rothschild Esq., written from Donaghadee, Ireland June 30th 1821

Nathan, ever the shrewd financier, was not taken in and there is no evidence that House of Rothschild invested in, or promoted MacGregor’s schemes. Despite Rothschild’s coolness, hundreds invested their savings in supposed Poyaisian government bonds and land certificates. The Legation of Poyais even chartered two boats to take settlers to Poyais. Why they would take this risk, knowing that the settlers would discover the truth about Poyais once they arrived, is scarcely creditable, but perhaps MacGregor had begun to believe his own myth. On September 10, 1822, the Honduras Packet departed from London with 70 settlers including doctors, lawyers and a banker. On January 22, 1823, the Kennersley Castle left Leith Harbour in Scotland with almost 200 settlers. When they arrived, the settlers, some of whom had risked their life savings, found an uninhabitable jungle that had more tropical diseases than riches. Of the original 240 settlers who reached Poyais, only 60 survived the insanitary conditions, dysentery and fever, and 50 eventually returned to London, the others remaining in British Honduras.

MacGregor left London shortly before the small party of Poyais survivors arrived home in October 1823 telling acquaintances that he was taking Josefa to winter in Italy for the sake of her health, but in fact his destination was Paris, where he continued to seek investors for Poyais before being arrested and remarkably, tried and acquitted. MacGregor quietly moved his family back to London, where the furore following the Poyais survivors' return had died down. In 1828 MacGregor began to sell certificates entitling the holders to ‘land in Poyais Proper’, but began to suffer from competition by other charlatans who set up their own rival ‘Poyaisian offices’ offering land debentures. By 1834 MacGregor was living in Edinburgh, but still selling Poyaisian land certificates. Josefa MacGregor died in Edinburgh, on 4 May 1838. MacGregor almost immediately left for Venezuela, where he applied for citizenship and restoration to his former rank in the Venezuelan Army, with back pay and a pension. The Venezuelan Senate was persuaded to look upon his application favourably and MacGregor was duly confirmed as a Venezuelan citizen with an army pension. He settled in Caracus and became a respected member of the local community. When he died in 1845, he was buried with full military honours in Caracas Cathedral. The part of today's Honduras that was supposedly called Poyais remains undeveloped to this day.

David Sinclair’s The Land That Never Was: Sir Gregor McGregor and the Most Audacious Fraud in History explains more about this most remarkable of fraudsters.

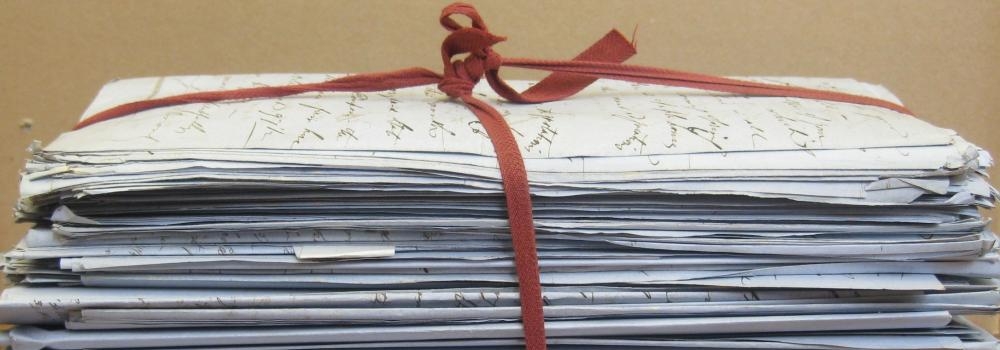

XI/112/54 Sundry correspondence ‘M’, 1821