Transcript of a report of the attack on the night of 10th May, 1941, by P.C. Hoyland, New Court.

NEW COURT

GREAT WAR

1939-1945[1]

Attack by the German Luftwaffe on the

City of London on the night of Saturday

10th May, 1941

Introduction

Before coming to the events of the night of 10th May, for the purpose of record and interest, it would be well to state briefly the precautions and steps taken for the protection of New Court prior to the outbreak of war.

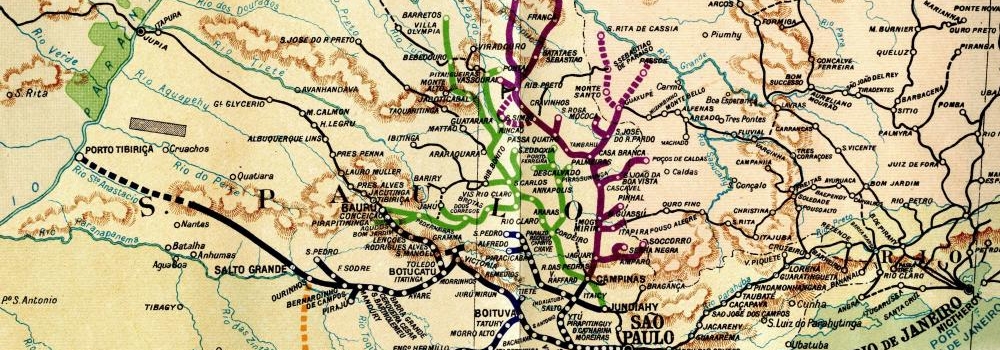

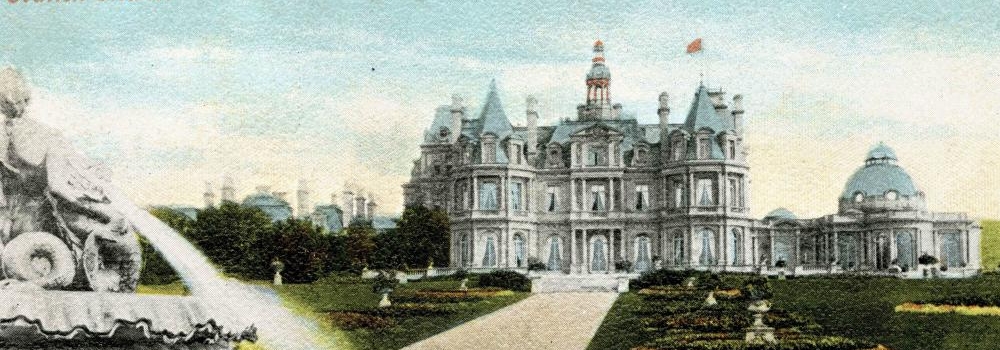

Approximately a week before war was declared in September 1939, about sixty percent of the clerical staff and all current records and books of value were evacuated to the seat of Lord Rothschild at Tring Park. Precautions for the protection of New Court and the remaining personnel had already been taken; the office having been equipped with fire-fighting apparatus, gas-proof curtains hung, a first-aid room installed and the dining room in the basement strengthened to take the weight of the building. Full equipment, such as tin hats, gas-masks etc. were available for the fire-watching staff.

During the Battle of Britain air-raid warnings were frequent and immediately the sirens were sounded, in accordance with a pre-arranged plan, the staff evacuated the upper storeys, of New Court and carried on their work in the dining room or other parts of the building which were considered to be less vulnerable from the effects of broken glass and blast.[2] Gradually familiarity bred contempt and unless enemy aircraft was reported immediately in the vicinity of the City, for which purpose a watcher was detailed on the roof, work proceeded normally. In order to have adequate assistance in dealing with fire at New Court it was arranged that at least six members of the clerical or outside staff, including the night watchman, should always be available for duty.

On the night of the 29th December 1940 the fist big fire attack took place on the City of London. As a result of high explosive bombs and a landmine in Sherbourne Lane which demolished the back of the City Carlton Club and the adjoining buildings, New Court suffered damage to a minor extent; the majority of the glass roof in the General Office was destroyed, the shutters in St. Swithin’s Lane were blown out and a number of windows in the courtyard broken, whilst the mahogany doors leading into the yard itself were badly damaged. Two incendiary bombs which fell on the roof of New Court alongside St. Swithin’s Lane, causing slight roof and water damage, were successfully dealt with through the efforts of the fire protection squad.

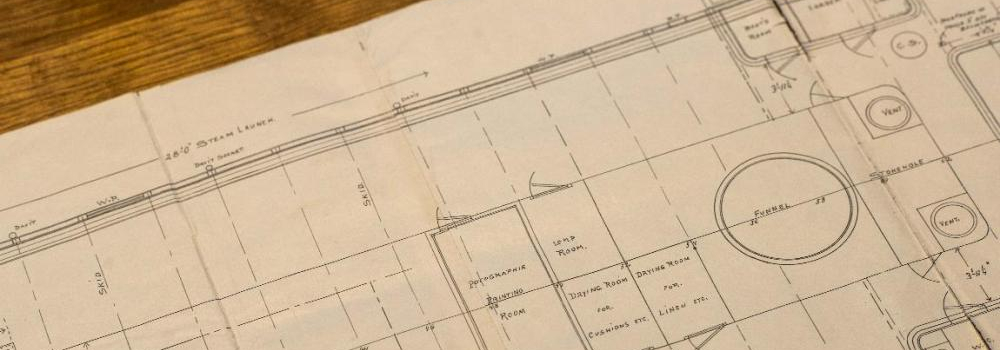

Through the experience gained on this occasion it was decided to supplement the equipment and precautions. Accordingly, cat-walks were erected around the roofs of the whole of the courtyard and iron ladders, giving easy access thereto, were installed.[3] Iron ladders were also placed in the courtyard thereby giving quick access to the roofs of the Bullion Room and Dividend Office, whilst the fire-fighting appliances were increased and made readily available. It was further felt that any incendiaries penetrating the roof and lodging between the roof and the ceiling on the third floor, would probably obtain such a hold before they could be adequately dealt with that the building might be endangered. Accordingly the ceilings of the whole of the upper floor were removed, leaving the rafters exposed. Thus, incendiaries which penetrated the roof would drop through to the third floor where they could be tackled under better conditions than on the roof itself. The City Corporation requested permission to erect in the courtyard a container holding 5,000 gallons of water which would serve both New Court and surrounding buildings, it being considered more effective to feed the fire engines from a tank whilst the tank itself would be re-filled from any available water supply.

On the night of 16th April another high explosive bomb fell in Sherborne Lane, the result of which completed the destruction of those buildings previously damaged. The effects of this were felt at New Court though damage, to the extent of a few broken windows, was very slight.

SATURDAY, 10th May

It is now proposed to deal fully with the events at the time of writing which most intimately affected New Court, namely, the attack by the Luftwaffe on the City of London during the night of 10th May.

It was a bright moonlight night with a moderate north east wind blowing down St. Swithin’s Lane from King William Street. There were on duty at New Court: Mr. H.E. Davies, Mr. P.C. Hoyland, Fireman F.W. Mason, Dutymen B.W.L. Hocking and A. Watkins and on fire duty A. Cornish.

The balloon barrage, which was visible in the moonlight, appeared to be low in comparison with its usual height, and, owing to the lack of traffic in front of the Mansion House since the demolition of the tube subway, the City was unusually quiet. At about 10.45 p.m. a single German aeroplane was heard over the capital and our anti-aircraft guns went into action. Almost immediately afterwards an air-raid warning was sounded, and from then onwards the sky was full of planes. It was now quite evident that a heavy attack was to be made on the. City, and although there were hundreds of planes in the sky it was easy to distinguish, by the sound of the engines, the heavy German bombers from our own fighters which seemed to be equally in force.[4] Incessant bursting of shells from our anti-aircraft could be clearly seen from the courtyard, though actually there did not seem to be any guns in close proximity. Soon the crash of high explosive bombs was heard, flares were dropped followed by showers of incendiaries which lit up the whole of the sky. The main early attack appeared to be in the direction of St. Paul' s Churchyard and lower Queen Victoria Street, and a large number of bombs were of the screaming variety. The air was soon filled with smoke and dust of demolished buildings and from time to time, amidst the crashes of the bombs, our fighters could be heard machine-gunning the German planes. Suddenly the enemy planes would dive and one instinctively knew that another load of high explosives would be released.

At one time there was a blinding flash and a terrific explosion. A shower of missiles consisting of blocks of concrete and bits of pavement, were hurled into the air. Some of these landed in the courtyard, others on New Court itself, whilst the blast swept right over the building. This was the first high explosive to be dropped in the immediate vicinity and it fell, as was subsequently discovered, opposite the front entrance to the Mansion House. Obviously it was necessary to take what cover was available and at this time it was considered advisable for the squad to divide itself into two, one lot taking shelter in the porters' archway and the remainder in the basement under the men's lodge.

About midnight, after a number of high explosives had fallen in Walbrook, a shower of incendiaries descended; none, however, actually fell on New Court, but from the white lights which appeared immediately all around it was evident that some had fallen in close proximity. It was then discovered that an incendiary was burning in the courtyard of Salters' Hall, and as there was no sign of any fire-watchers there, this was extinguished by means of sand and a stirrup pump by the New Court squad.[5] Incendiaries at this time must have lodged in the roof of St. Swithin's church at the bottom of the lane as by now it was blazing fiercely and flames were soon roaring skywards lighting up the whole neighbourhood.[6] In spite of repeated attempts to try and attract attention, no fire-watchers appeared at Salters' Hall.

The squad had only just returned to New Court when a further shower of incendiaries were let loose and it was soon evident that a number of these had not only dropped in the immediate vicinity but had struck New Court itself. The first real intimation of this was a flickering seen through the broken shutters at the top of the building. Immediately all members of the squad dashed to the top floor of the office where it was found that two incendiaries had penetrated the roof and were lodging on the top floor; one in the far room on the south side of the courtyard and the other in the far room on the north side. These were immediately tackled with sand and stirrup pumps and were successfully got under control before any real damage was done. It is believed, but it is impossible to verify, that this shower of incendiaries was responsible for the fire which ultimately destroyed Salters' Hall and the building at the end of the Dividend Office.

From the fire and smoke which now enveloped the whole of the City it was quite evident that the fire services had little control and, owing to the high wind, the flames were spreading rapidly. The building at the rear of the Dividend Office was now a mass of flames and flames were licking across the passage between that building and Bow Church in Walbrook which was soon also ablaze.[7] All this time intermittent high explosives had been falling both in the vicinity and over the City generally.

Reports of these fires were sent to the fire brigade but it was obvious they were fully occupied; moreover there appeared to be a general shortage of water, and although at about this time it was low tide, every effort was being made to pump from the river.

At about 4.0 a.m. the flames from Salters' Hall and the adjoining buildings were so menacing that it was decided to try and get assistance in view of the proximity to our Bullion Room. The Auxiliary Fire Service squad from Hornsey, who had been sent to deal with St. Swithin's Church which was now just a flaming torch, was persuaded to deal with the fire at the rear of the Dividend Office and to endeavour to save St. Stevens [sic], Walbrook which had not yet reached a dangerous conflagration.[8] Fortunately the officer in charge consented to do this and brought their pump into the yard. They took the hose through the window of the passage at the end of the General Office, and by means of the water in the tank at New Court soon had the fire in the building at the rear of the Dividend Office in hand. They also succeeded in putting out the fire at St. Stevens [sic].

The time was now between 5.0 and 6.0 a.m. and although planes were still intermittently passing over, the main attack seemed to have spent itself. The greatest danger at this time appeared to be from Salters' Hall. This fire had started at the end farthest away from New Court but the flames had now reached the wall adjoining the Bullion Room and were rapidly enveloping the whole of the main building and the adjoining building abutting the wall in the courtyard. With the lack of water it was decided to request the Refinery, who had already been warned that their pump might be required, to bring the pump to New Court for the purpose of pumping water from the unused tank in the Mansion House yard into the tank at New Court.[9] This was successfully done and enabled the A.F.S [Auxiliary Fire Service] to play their hoses on to Salters' Hall thus keeping the fire from spreading and preventing the party walls to our strong room from overheating.

The all-clear went about 6.0 a.m. and from then onwards, owing to lack of water, there was little one could do but watch the flames gradually spread. The fire at Salters' Hall was now spreading towards the back of De Beers in St. Swithin's Lane - these offices had been evacuated and had been taken over as a Police Station.

At about this time the A.F.S. required some additional length of hose and after searching Queen Victoria Street a call was made to the fire station opposite the Mansion House Tube Station; Their reply was “if you want any hose the only thing to do is to scrounge it”: this was successfully done by the A.F.S. squad by the time the message reached them.

Although the tank at New Court had been emptied for the second time on Salters' Hall the building was still ablaze. A relay of helpers then carried water from the bottom of the New Court tank to Salters Hall for use in stirrup pumps, and although this supply was somewhat inadequate, a certain control of the fire was maintained.

During the early morning the wind veered round from north east to south west. This undoubtedly saved the block of buildings in which the De Beer Mines Offices were situated but made the position of New Court, which was surrounded by fire, more precarious. The fire from Salters Hall and from Walbrook had now spread through Bond Court northwards and. St. Stevens [sic] had once again caught alight. At the same time the flames from Salters' Hall and the building at the rear of the Dividend Office were fanned into fresh conflagrations, again threatening the strong room and the archives.[10] Once more the A.F.S., who by this time were able to pump a certain amount of water from the Thames into the tank at the Mansion House yard, carne to our assistance and no further damage was done.

It should be mentioned that amongst other buildings in the neighbourhood, Cannon Street Hotel and London Stone were burnt out and Walbrook was completely demolished from the effects of high explosives and fire.[11] Added to the difficulties in Walbrook was the fact that an unexploded high explosive bomb which fell during the early hours of the raid was expected to detonate at any moment owing to the intense heat. It is regretted that two fire-watchers lost their lives in Walbrook.

It was not until about mid-day on Sunday that New Court was considered to be out of danger, and with grateful thanks the Hornsey A.F.S. went off duty. Even at that time the air was thick with smoke from burning paper etc. and dust of demolished buildings.

It was expected that on Sunday night the Germans would repeat their attack on London, and, at about mid-night, it was with some trepidation one heard the sirens sound the alert and planes and gunfire in the distance. Prior to this, flames, which had been bursting out at intervals during the day from buildings which had been considered under control, appeared at the windows of the London Stone. Although this looked like developing into a big fire, the flames were satisfactorily dealt with by means of appliances which had now been brought into the City.

Fortunately the raid did not materialise and although an alert was on during most of the night no bombs were dropped in the neighbourhood.

[signed] P.C. Hoyland

[1] At the time of the compilation of this report, the end date of the war was unknown. The date ‘1945’ appears, written in manuscript in biro, presumably added when hostilities had ceased.

[2] ‘The Battle of London’ is typed and 'London' is crossed out, and ‘Britain’ written in manuscript above it in biro, presumably added when the battle had received this nomenclature.

[3] A ‘cat-walk’ is a narrow walkway, often installed above roofs or industrial premises to aid access or inspection.

[4] There seems to be some later dispute about the number of planes; ‘?’ has been added in manuscript in biro above the word ‘hundreds’.

[5] The Worshipful Company of Salters, one of the twelve medieval Great Livery Companies of the City of London, was first licensed as a Guild in 1394, to protect its members who worked in the salt, pepper and spice trade. The first Salters’ Hall, near the wharves on the Thames, burnt down in the Great Fire of London in 1666. The second Salters’ Hall, a classical Georgian building between St Swithin’s Lane and Walbrook, opened in 1827 but was completely destroyed during the Blitz in 1941. A new Salters’ Hall in London Wall Place opened in 1976.

[6] The Church of St Swithin stood on the north side of Cannon Street, between Salters' Hall Court and St Swithin's Lane. Of medieval origin, it was destroyed by the Great Fire of London, and rebuilt to the designs of Sir Christopher Wren. The Church was badly damaged in the Blitz. After the war it was not rebuilt; instead the parish was united with that of St Stephen Walbrook in 1954. The ruined church was finally demolished in1962. 111 Cannon Street now occupies the site, and the former churchyard retained as a public garden.

[7] It is not clear as to which church Hoyland is referring to here. St Mary-le-Bow Church is in Cheapside, some distance away. Hoyland may be referring to St Stephen Walbrook.

[8] St Stephen, Walbrook was erected to the designs of Sir Christopher Wren following the destruction of its medieval predecessor in the Great Fire of London in 1666. It is located in Walbrook, next to the Mansion House. The church suffered slight damage in the Blitz and was later restored. When Rothschild & Co opened the fourth New Court building in 2011, views of the Church from St Swithin’s Lane, unseen for over 150 years, were restored.

[9] The pump had been sent from another Rothschild business, The Royal Mint Refinery, located in Royal Mint Street some distance to the east. The Rothschild run Royal Mint Refinery had been established in 1852, and for generations had produced gold bullion largely on behalf of sovereign clients. During the war, production switched to the manufacture of armaments. The business survived the war and the product range was diversified, but the refinery was sold by the London Rothschilds in the late 1960s.

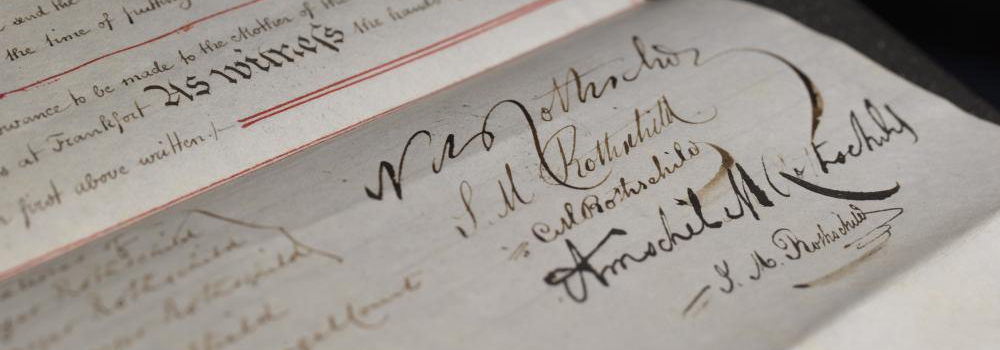

[10] In actual fact many of the historic archives had been sent to Tring Park and Exbury House for safekeeping during the war, but many papers were retained at New Court for the continuance of business.

[11] ‘Cannon Street Hotel’ refers to the Cannon Street Station Hotel which opened as the City Terminus Hotel, in May 1867. It was an Italianate style hotel and forecourt, designed by E. M. Barry, and it provided many of the station's passenger facilities, as well as an appropriate architectural frontispiece to the street. The station suffered extensive bomb damage, and the remains of the hotel (used for offices) were demolished in 1960. The station, fronted by a new office block was rebuilt in 1965. The ‘London Stone’, now housed at 111 Cannon Street, is an irregular block of oolitic limestone, the remnant of a once much larger object that had stood for many centuries on the south side of the street. The date and original purpose of the Stone are unknown, although it is possibly of Roman origin, and there are claims that it was formerly an object of veneration or has some occult significance.