The management of private investments was the foundation upon which Rothschild banking was built. Since the formation of the first partnership, the Rothschild banking houses managed the assets of, and provided credit to, a small and distinguished clientele, which included members of Royal houses across Europe.

Bankers to Royalty

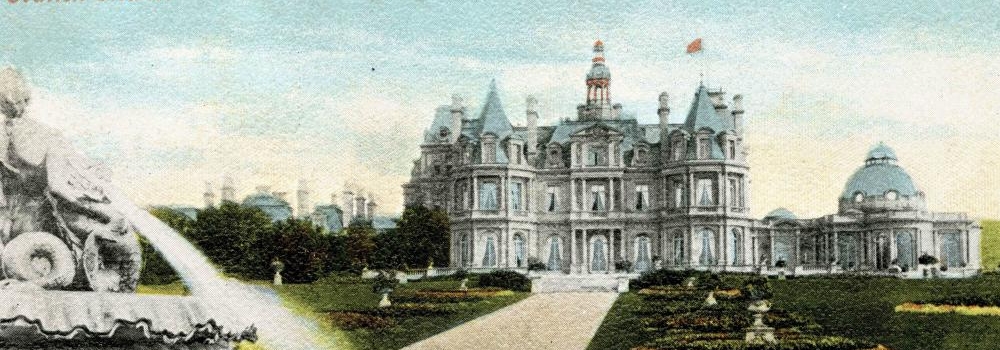

Through his father's banking house in Frankfurt, in 1816 Nathan Mayer Rothschild (1777-1836) became banker to Leopold I of Belgium (1790-1865). King Leopold’s financial adviser, Baron Stockmar (1787-1863), an associate of Baron Lionel de Rothschild (1808-1879), was also a leading player in the affairs of Queen Victoria (1819-1901). Royal patronage of Rothschild services was enhanced in 1840 when Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg (1819-1861) married Queen Victoria, and the Rothschild banks in London and Frankfurt subsequently handled select payments on behalf of the royal couple. The Royal family relied on the many services provided by the Rothschilds, such as the provision of chocolate for the Queen’s mother’s breakfast and a secure courier service. In 1852, the London house discreetly provided a loan to the Prince Consort for the purchase of the Balmoral estate. In 1885, Queen Victoria, acting on the advice of Gladstone’s Government, raised Nathaniel (‘Natty’) Rothschild to the House of Lords as the first Jewish peer, Lord Rothschild of Tring. Lionel de Rothschild also kept a discrete but watchful eye over the finances of the Queen’s eldest son, the Prince of Wales, who in 1881 had attended the wedding of Leopold de Rothschild (1845-1917) to Marie Perugia (1862-1937).

The Coronation of 1902

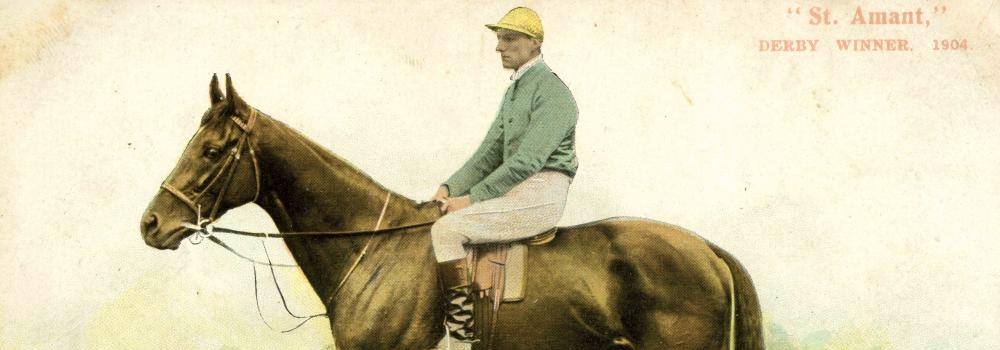

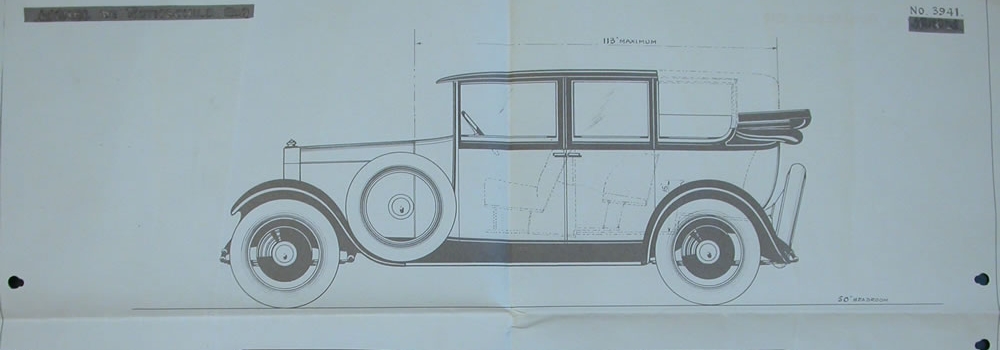

In 1901, the Prince of Wales became King Edward VII upon the death of Queen Victoria. During the long reign of his mother, the Prince was largely excluded from political power. He travelled throughout Britain performing ceremonial public duties, and represented Britain on visits abroad, but despite public approval, gained a colourful reputation as a playboy prince. His reign coincided with the start of a new century which was to herald significant changes in technology and society. The planned Coronation ceremony was delayed because of the new monarch’s ill-health; Edward VII was crowned with his consort Queen Alexandra, at Westminster Abbey on 9 August 1902, two weeks after he had suffered from an abdominal cyst, which was, unusually for the era, operated upon successfully on a table in the Music Room at Buckingham Palace. An unintended effect of the postponement was the departure of the foreign delegations; they didn't return for the rescheduled ceremony, leaving their countries to be represented by their ambassadors. This made the coronation ‘a domestic celebration’ according to J. E. C. Bodley, the official historian of the event. The service was conducted by the elderly and infirm Archbishop of Canterbury, Frederick Temple, who refused to delegate any part of his duties and was unable to rise after kneeling to pay homage and had to be helped up by the King himself and several bishops. Because of his failing eyesight, the text of the service had to be printed in gigantic type onto rolls of paper called ‘prompt scrolls’ and he inadvertently placed the crown back-to-front on the King's head. Throughout the country there were celebration fetes and galas, and preserved in the Archive is a photograph album of Mr Warren, Head Gardener at the Rothschild estate at Aston Clinton recording the village’s Coronation celebrations which included speeches, competitions and in the evening, a Grand Illuminated Cycle Parade.

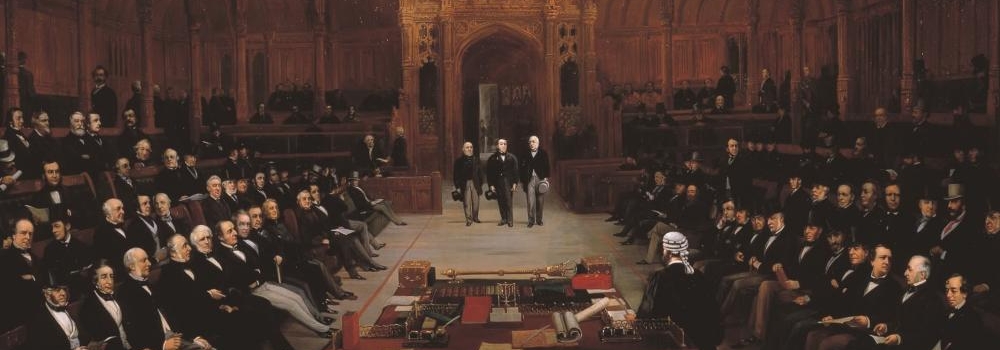

As King, Edward played a role in the modernisation of the British Home Fleet and the reorganisation of the British Army. Edward fostered good relations between Britain and other European countries, especially France, but his relationship with his nephew, the German Emperor Wilhelm II, was poor and exacerbated the tensions between Britain and Germany. The new King had a tremendous zest for pleasure but he also had a real sense of duty. He donated his parents' house, Osborne on the Isle of Wight, to the state and continued to live at Sandringham. Edward refurbished the royal palaces, reintroduced the traditional ceremonies, such as the State Opening of Parliament, and founded new honours, such as the Order of Merit, to recognise contributions to the arts and sciences. He could afford to be magnanimous; his private secretary, Sir Francis Knollys, claimed that he was the first heir to succeed to the throne in credit. Edward's finances had been ably managed by Sir Dighton Probyn, Comptroller of the Household, and had benefited from advice from Edward's Jewish financier friends, Ernest Cassel, Maurice de Hirsch and the Rothschilds; Nathaniel, 1st Lord Rothschild and other members of the Rothschild family found favour at Court.In the Coronation honours of 1902, Nathaniel was appointed to the Privy Council of the United Kingdom, the formal body of advisers to the Sovereign.A heavy smoker, Edward VII died in 1910 after a series of heart attacks exacerbated by severe bronchitis. The King’s funeral was one of the largest gatherings of European royalty ever to take place, and one of the last before many royal families were deposed and scattered in the First World War and its aftermath.

The Rothschild Partners at New Court were greatly saddened by the King’s death. Natty wrote to his French cousins on 9 May (three days after the king’s death) “the late King’s talents not to say his generosity were known all over the world and could not fail to be appreciated. He will go down to history as Edward the Peacemaker and none of the many illustrious Sovereigns of England of the name of Edward, perhaps none of his predecessors ever had large a grander title. To us Jews apart from anything else his memory will always be sacred. A great friend of religious liberty, he was always anxious to receive our fellow co-religionists in any part of the world.”

Edward The VII ‘Coronation’ Silver and gold coin set, 1902

In the Archive collection is a small red leather box, containing a collection of thirteen ‘Specimen coins 1902’ an uncirculated set of the coinage of the day, specially issued to mark the Coronation. Each coin bears a portrait of Edward VII by George William De Saulles on the obverse; the reverse on each coin bears the following engravings: Five Pounds (Quintuple Gold Sovereign) - St George and Dragon; Two Pounds (Double Gold Sovereign) - St George and Dragon; Gold Sovereign - St George and Dragon; Gold Half Sovereign - St George and Dragon; Silver Crown - St George and Dragon; Silver Half-Crown - Crowned Shield in Garter; Silver Florin - Standing Britannia; Silver Shilling - Lion on Crown; Silver Sixpence - Crowned Value ‘Six Pence’ in Wreath; Maundy Fourpence - Crowned Value ‘4’ in Wreath; Maundy Three Pence - Crowned Value ‘3’ in Wreath; Maundy Twopence - Crowned Value ‘2’ in Wreath; Maundy Penny - Crowned Value ‘1’ in Wreath. It is not clear how the set came to be at New Court; it may have been a gift to the Partners. It was displayed in the vitrine in the hall of the second New Court, and disappeared into the vaults when New Court was rebuilt in the 1960s.

The ‘missing’ sixpence

When the set arrived in the Archive, it was missing the silver sixpence. A Christmas tradition, believed to have been brought over to Britain by Prince Albert may explain its absence. On the Sunday before Advent, families gathered in the kitchen to help make the Christmas pudding. A silver sixpence was placed into the pudding mix and every member of the household gave the mix a stir. Whoever found the sixpence in their own piece of the pudding on Christmas Day would see it as a sign that they would enjoy wealth and good luck in the year to come. It is tempting to speculate that in days gone by, the New Court cook ‘borrowed’ the 1902 silver sixpence and some lucky clerk found it in their Christmas lunch! The sixpence has been replaced and the set is once more complete.

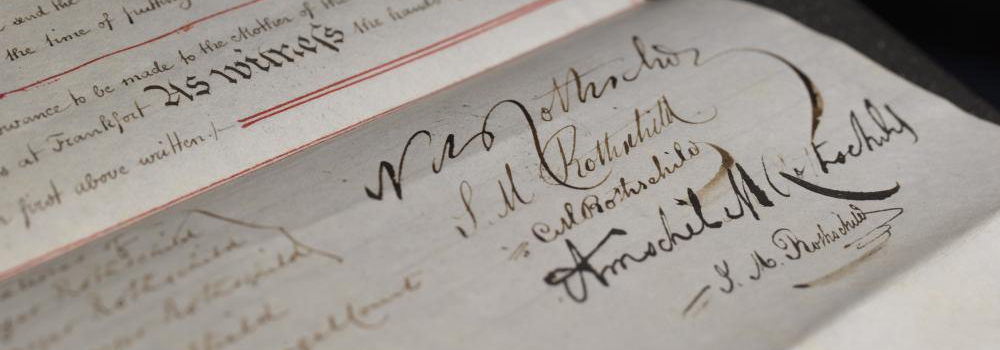

RAL 000/1911/50