In this Choice, we recall the great collections assembled by the Rothschild family, and the role that the London house of Rothschild played 175 years ago in helping to bring about the establishment of one of the great repositories of knowledge in the world – The Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C.

The Rothschilds as collectors

The Rothschild family were dedicated collectors. The great Rothschild mansions were perfect settings for silverware, porcelain and works of art. Not content with merely gathering, the family acquired the skills to develop collections of significance, adding to the knowledge of curators and scientists worldwide.

Paintings, books, manuscripts and objets d’art

From their bases in London, Paris, Vienna, Frankfurt and Naples, the Rothschild family assembled collections including some of the most famous masterpieces: Flemish and Dutch old masters, art of 18th century France, and 18th century English portraitists, together with a fondness for Sèvres porcelain. The French family in particular favoured the collection of books and manuscripts. James Edouard de Rothschild (1844-1881) had an impressive library, inheriting from his grandfather James Mayer (1792-1868) exquisite ‘Books of Hours’. Another great family passion was for Schatzkammer ('Treasure Room') objects. In collecting these pieces, the Rothschilds were influenced by the wealthy Renaissance princes who kept cabinets of curiosities. The collection of Lionel de Rothschild (1808-1879) included ivories, mother-of-pearl, rock crystals, mounted tusks, horns, shells, Renaissance jewels, snuffboxes, Venetian and Flemish glass, and majolica. Ferdinand de Rothschild (1839-1898) collected throughout his life, inheriting many pieces from his father, Anselm. His collection reflected the achievements of goldsmiths of the early Renaissance and Baroque periods.

Many of the Rothschild collections were given, with a sweep of generosity conceived on the same scale as their acquisition, to museums and galleries. Henri de Rothschild (1872-1947) bequeathed over 24,000 volumes to the Bibliothèque Nationale. Edmond de Rothschild (1845-1934) collected 46,000 prints and drawings which he gave to the Musée du Louvre; his brother Mayer Alphonse (1827-1905) accumulated over 2,000 works of French painting and sculpture, which he gave to over 150 museums. Ferdinand de Rothschild gave to the British Museum the Waddesdon Bequest » Collections of the French Rothschild family can now be found in the Musée du Louvre »

N M Rothschild and the Smithson legacy

The Smithsonian Institution in Washington was founded on 10 August 1846 with funds bequeathed by the English scientist, James Smithson (1765–1829). Today, it is the world’s largest museum and research complex, holding 156 million artefacts, specimens and books. The Institution comprises 19 museums, 21 libraries, 9 research centres, and a zoo. It receives 30 million visitors each year, and displays iconic American treasures such as the Star-Spangled Banner, Abraham Lincoln’s stove-pipe hat, Judy Garland’s ruby slippers from The Wizard Of Oz, the original Teddy Bear named after Theodore Roosevelt, and the large model ‘Enterprise’ from the original Star Trek TV series.

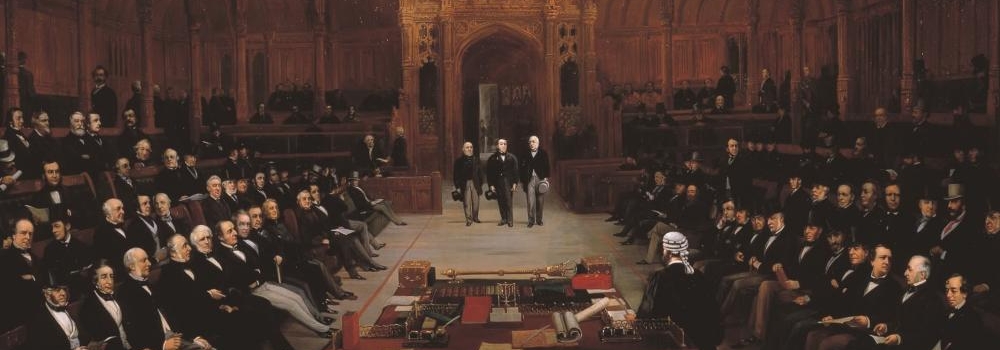

In 1834, on the election of President Andrew Jackson, the London house of Rothschild was awarded the commission to represent United States' banking interests in Europe, hitherto in the hands of Baring Bros. Part of their responsibility was to administer the payments made by the government to its consular staff in Europe. Occasionally the task was to have a more lasting effect, as when the bank was assigned funds to assist the United States government in its claim to the legacy of James Smithson; with Rothschild help the funds were secured for the government.

When he died in 1829, James Smithson left most of his wealth to his nephew Henry James Hungerford. However, should his nephew die without children, a contingency clause in his will stated that the estate would go "to the United States of America, to found at Washington, under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an Establishment for the increase & diffusion of knowledge among men". When Hungerford died childless in 1835, in accordance with Smithson's wishes, the estate passed to the U.S. Government. After much debate, Congress officially accepted the legacy bequeathed to the nation and on 1 July 1836 pledged the faith of the United States to a charitable trust, for the purposes of creating the Smithsonian Institution.

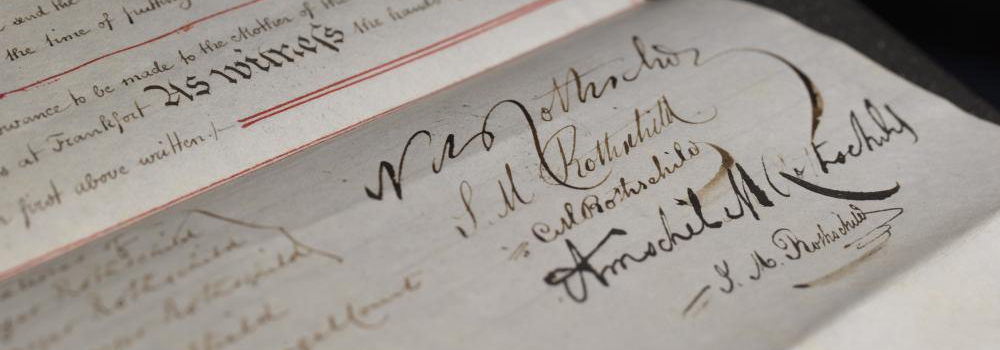

Andrew Jackson dispatched the American diplomat and former Treasury Secretary, Richard Rush to England to secure the funds; however, this proved no straightforward commission. The mother of Henry James Hungerford, Smithson's designated heir, filed a counterclaim, and Rush spent two years in England pursuing the United States' claim in the Court of Chancery. His expenses, which amounted to about $10,000, were handled by N M Rothschild and confirmed in the letter reproduced below. Nonetheless, Rush won the United States' claim in a remarkably short time, and on 9 May 1838, the Court awarded Smithson's properties to the United States. Rush sold the properties, converting the proceeds into gold sovereigns. Rush returned to the U.S. in August 1838 (the voyage taking six weeks) with 105 sacks containing 104,960 gold sovereigns, and Smithson’s scientific collections and library. Rush personally posted a $500,000 bond as insurance that he would not abscond with the Smithson bequest. Upon his arrival in New York, Rush transferred the gold to the U.S. Treasury in Philadelphia. The coins were melted down to yield a value of $508,318.46. The Smithsonian Institution has estimated the value of the legacy as $220 million today.

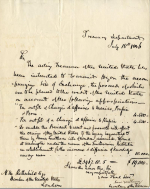

Letter from Levi Woodbury to Nathan Mayer Rothschild, July 18, 1836

N M Rothschild Esq

Banker of the United States

LondonTreasury Department July 18th 1836

Sir,

The acting Treasurer of the United States has been instructed to transmit to you the accompanying bill of Exchange, the proceeds of which are to be placed to the credit of the United States on account of the following appropriations --

"For outfits of Chargés d'Affaires to Mexico, Prussia, & Peru 4.500"

"For outfit of a Chargé d'Affaires to Russia 4.500"

"To enable the President to assert and prosecute with effect the claims of the United States to the legacy bequeathed to them by James Smithson late of London deceased, to found at Washington under the name of the Smithsonian Institution an establishment for the increase & diffusion of knowledge among men . . .10,000"£3967.10.5 = $19,000

I have the honor Dear Sir very respectfully,

your obedient Servant

Levi Woodbury Secretary of the Treasury

The Smithson bequest caused great debate in the U.S. right up until the opening of the Institution in 1846. Press and public on both sides of the Atlantic were startled by the rather unusual provision in the will, with U.S. newspapers urging that the bequest be “faithfully carried into effect.” Although Smithson had an underlying philosophy that pursued the development of scientific knowledge, he did not explain the reasons for his bequest in his public or private writings; his motives in leaving money to the United States (a country in which he had never set foot) are unknown. Some 75 years after his burial in Genoa, Alexander Graham Bell brought Smithson's remains to Washington, where they were interred in a tomb in the Smithsonian Building.

Experience the collections of the Smithsonian Institution » and find out more about the extraordinary story of the Smithson will and legacy » Londoners will soon be able to enjoy the Smithsonian’s first permanent overseas exhibition space; the Institution has confirmed plans to co-curate a gallery with the Victoria and Albert Museum in its new museum, part of East Bank, in the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in East London when it opens to the public in 2023.

RAL XI/38/1/1/90 letter from Levi Woodbury to Nathan Mayer Rothschild, 18 July, 1836