The story of Rothschild involvement with enterprises such as railways and refining is well-known. But throughout their history, the Rothschild businesses have also helped companies producing familiar, everyday items. This month, as a bidding war emerges for control of the UK's fourth-largest supermarket, Morrisons (advised by Rothschild & Co.), we explore the assistance given to the venerable English biscuit-making firm Peek Frean & Co. Ltd, and how N M Rothschild & Sons brought relief to citizens during the Siege of Paris in 1870.

N M Rothschild & Sons and Peek Frean & Co. Ltd

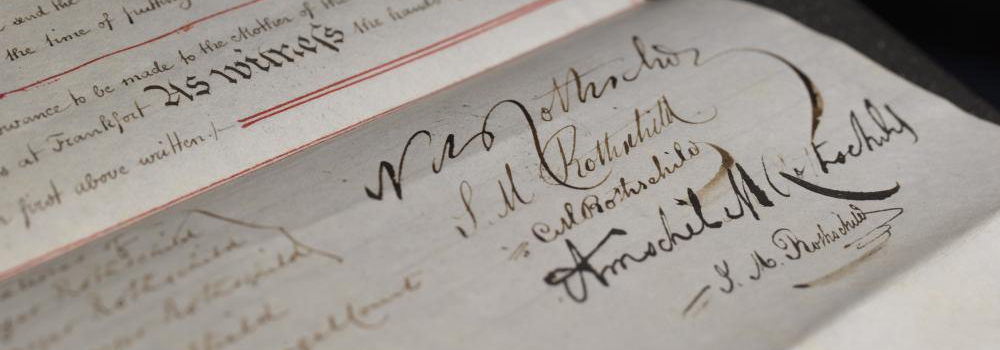

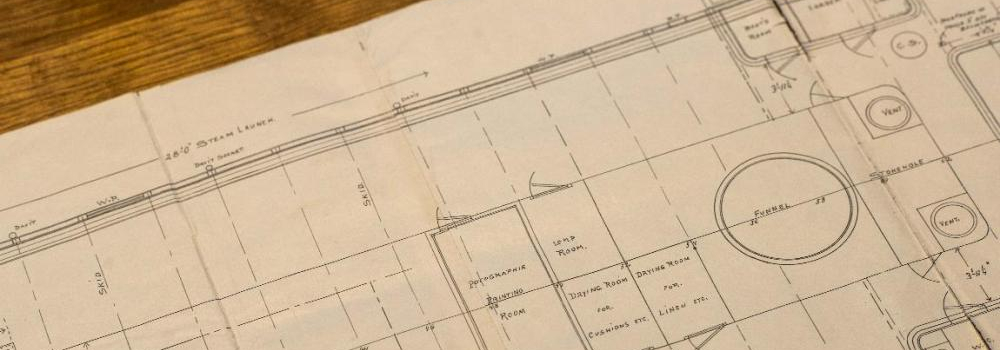

The London Rothschild banking house was founded by Nathan Mayer Rothschild (1777-1836) in St Swithin’s Lane in the City of London in 1809. The biscuit manufacturers Peek Frean & Co. Ltd. trace their origins to James Peek (1800-1879), one of three brothers born in Dodbrooke, Devon, who, in 1821 founded a tea importation company, Peek Brothers and Co., in the East End of London. In 1857, two of James Peek’s sons announced that they were not going to join the family tea business. Peek wanted them in a complementary trade and proposed that they start a biscuit business. Soon after the new venture was founded, one son died and the other emigrated to North America; one of Peek’s nieces, Hannah Peek, had recently married George Hender Frean, a miller and ship biscuit maker in Devon, so Peek asked him to manage the biscuit business. The partners registered their business in 1857 as Peek, Frean & Co. Ltd, based in a disused sugar refinery in Dockhead, in Bermondsey. From 1861, the company started exporting biscuits to Australia. By 1865, the company had outgrown their premises and a new integrated factory was commissioned. With the opening of the factory in 1866, its scale and its emanating sweet 'aroma' gave Bermondsey the nickname "Biscuit Town". Like many good employers of the Victorian age, the company provided innovative benefits to its employees; the factory had an on-site bank, post office and fire station; employees and their families had access to free on-site medical, dental and optical services, and sporting, musical and dramatic societies flourished.

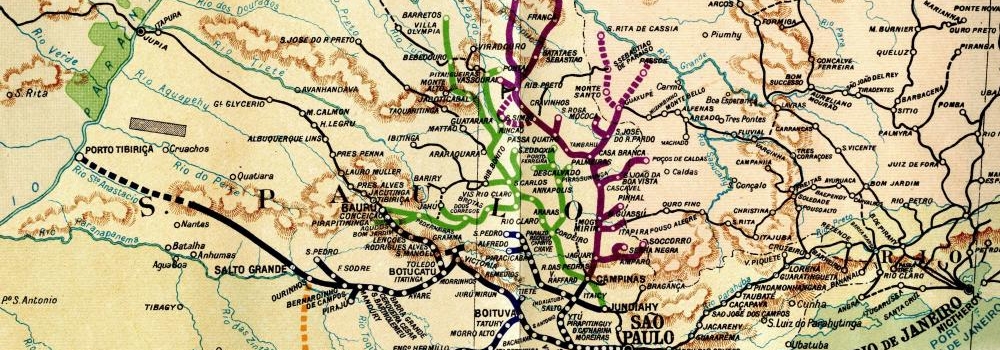

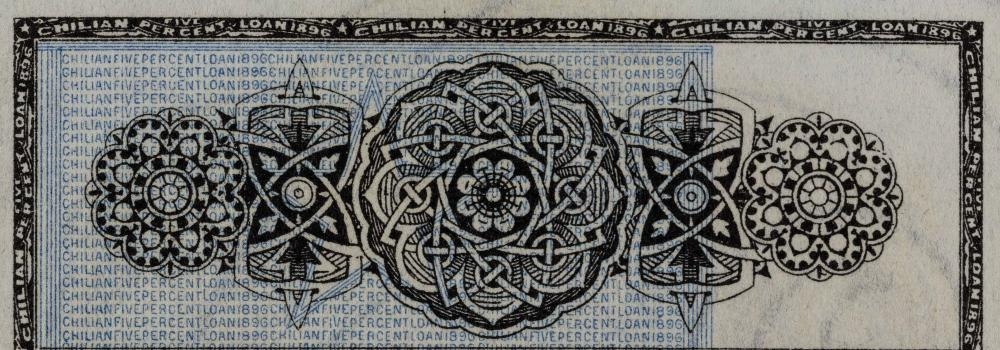

In 1870 the company agreed to fulfil an order from the French Army for 460 long tons of biscuits for the ration packs supplied to soldiers fighting the Franco-Prussian War. After hostilities ended, the French Government ordered a further 16,000 long tons (over 11 million ‘Sweet Pearl’ biscuits) in celebration of the end of the Siege of Paris, and further flour supplies for Paris in 1871 and 1872, with financing undertaken by Peek Freans’ bankers, N M Rothschild & Sons. In 1872, again with financing from the Rothschilds, the company began exporting biscuits to Canada, driven by demand for biscuits from French migrants. On 23 April 1873 the old Dockhead factory burnt down in a spectacular fire, which brought the Prince of Wales out on a London Fire Brigade horse-drawn water pump to view the resulting explosions. James Peek died in 1879 and after his partner George Frean’s son James retired in 1887, the family had nothing more to do with running the business. After 126 years of continuous production, with the biscuit market in decline, the London factory was closed by then owner BSN in 1989. The Peek Frean brand is today dormant in the UK market.

In 1906, the Peek Frean and Co. factory in Bermondsey was the subject of one of the earliest documentary films ever made, shot by Cricks and Sharp. This fascinating short film follows the process from the mixing of the raw ingredients to the finished products leaving the factory. Note the labour intensive process, how returned biscuit tins are washed and reused (an early example of recycling), and the then ultra-modern delivery lorries. The film can be viewed here » The Peek Frean Biscuit Museum can be viewed here »

The Siege of Paris

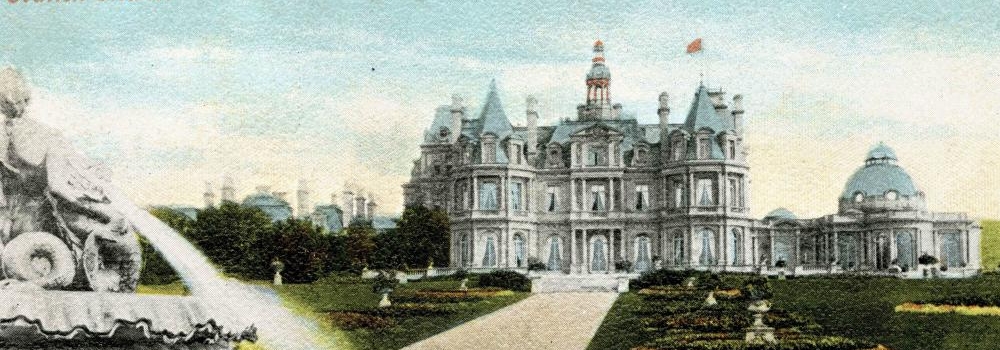

The Siege of Paris, which took place from 19 September 1870 to 28 January 1871 was an engagement of the Franco-Prussian War, 1870-1871 (known in France as 'The War of 1870'). After the defeat at the Battle of the Sedan, where French emperor Napoleon III surrendered, the new French Third Republic was not ready to accept Prussian peace terms. To end the Franco-Prussian War, the Prussians besieged Paris. As ambassador to Paris, Otto von Bismarck had stayed on numerous occasions at the Château de Ferrières, the sumptuous palais of James de Rothschild (1792-1868) on the outskirts of Paris; as Chancellor of Prussia, he persuaded the Prussian King to make the Château his headquarters during the invasion. The Prussian high command rejected the idea of a bombardment of the city, and resolved to starve Paris into surrender. Due to the severe shortage of food, Parisians were forced to slaughter whatever animals were at hand. Rats, dogs, cats, and horses were the first to be slaughtered and became regular fare on restaurant menus. Once the supply of those animals ran low, the citizens of Paris turned on the zoo animals residing at Jardin des plantes. Even Castor and Pollux, the only pair of elephants in Paris, were slaughtered for their meat.

A Christmas menu, from the 99th day of the siege featured ‘unusual’ dishes such as stuffed donkey's head, elephant consommé, roast camel, kangaroo stew, antelope terrine, bear ribs, cat with rats, and wolf haunch in deer sauce.

During the siege, the only head of diplomatic mission from a major power who remained in Paris was United States Minister to France, Elihu B. Washburne. As a representative of a neutral country, Washburne became one of the few channels of communication into and out of the city for much of the siege. He also led the way in providing humanitarian relief to foreign nationals. In London, N M Rothschild & Sons used their network of trusted suppliers, agents and couriers to secure much-needed relief. Bills of Lading (a detailed list of a ship's cargo in the form of a receipt given by the master of the ship to the person consigning the goods) survive in the Archive for food supplies sent to Paris by N M Rothschild & Sons; in July 1870, the firm sent 1000 barrels of prime salt pork, 1000 barrels of American flour and 700,000 lbs of preserved boiled mutton in tins to Paris as well as supporting firms such as Peek Freans in the production of supplies.

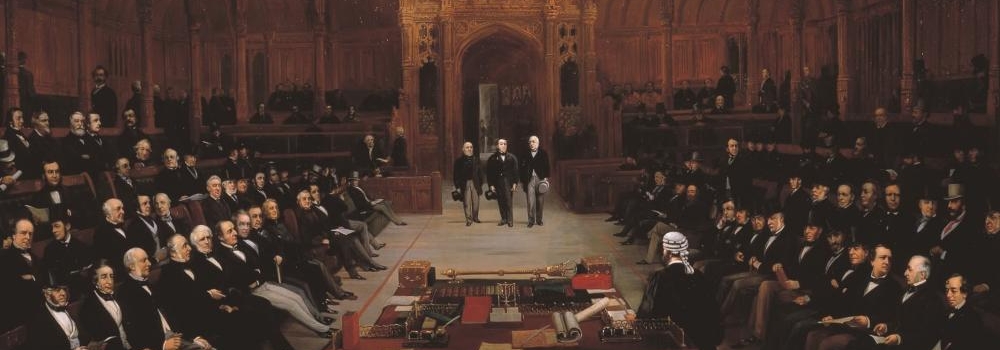

Wilhelm I was proclaimed Prussian Emperor on 18 January 1871 at the Palace of Versailles. Secret armistice discussions began on 23 January 1871 and continued at Versailles. The length of the siege helped to salve French pride, but also left bitter political divisions; the siege ended in the capture of the city by Prussian forces, culminating in France's defeat and the establishment of both the Prussian Empire and the Paris Commune. The final terms agreed on were that the French regular troops (less one division) would be disarmed, Paris would pay an indemnity of two hundred million francs, and the fortifications around the perimeter of the city would be surrendered. The final peace treaty, the Treaty of Frankfurt, was signed on 10 May 1871.

The novel 'Empires of Sand' by David W. Ball (Bantam Dell, 1999), the first part of which is set during the Siege of Paris, renders a vivid impression of war-time Paris before its surrender.

RAL XI/4/28, 'Affaires' Correspondence: Provisions shipped to France during the Franco-Prussian War, 1870-1871