In this Choice, we look back to the efforts of Nathan Mayer Rothschild to secure residency rights in England at the turn of the nineteenth century.

The arrival of Nathan Mayer Rothschild in England

Nathan Mayer Rothschild (1777-1836) was a complicated personality. An ambitious man, his determination and drive made him sometimes impatient of others, but his inventiveness meant that he was constantly looking forward to new opportunities. The young Rothschild, the first of his generation to leave the confines of the Frankfurt ghetto, arrived in Manchester in May 1799, after spending several months in London gaining experience of English trading methods. He arrived with capital of around £20,000 (over £1.5m today), part of his father’s attempt to consolidate and extend the family’s trade in English printed textiles. Nathan was accompanied by his father's chief bookkeeper, Siegmund Geisenheimer, and he opened a warehouse in Brown Street, in the commercial heart of the city, and rented a villa in Downing Street, Ardwick, then a fashionable residential suburb. From these bases he began to make his economic mark in a city bursting with entrepreneurial energy, establishing his firm N M Rothschild. In 1806, Nathan married Hannah (1783-1850), daughter of the London merchant Levi Barent Cohen, giving him a position in society and access to influential contacts. Following the death of his father-in-law, Nathan moved to London, taking premises at New Court, St Swithin’s Lane and established his finance house dealing in bullion and foreign exchange.

Migrant traders and the economic development of Manchester

The Rothschilds were not alone in their ambition to tap into Manchester's production of cotton textiles as the city rapidly expanded during the 1780s and 1790s under the impact of newly invented mechanical devices for spinning and printing. Nathan was one of a number of German merchants who opened warehouses in central Manchester at the turn of the eighteenth century to buy in and export Manchester goods. Like most of the others, he knew little English, had few, if any, local connections beyond the English agents he had come across in his native Frankfurt, and no knowledge of a town already becoming legendary as 'the shock city of the age'. However, his character and determination was to be his strength. Of the tens of thousands of 'immigrants' who had flocked into the city in the late 18th century, perhaps fifteen or twenty were from families of Jewish origin. It was probably in 1788 that a group of Jewish pedlars and shopkeepers of German and Polish origin moved on from Liverpool, to a city which seemed more likely to reward their retail enterprise. Settling closely together in cheaper property in the Old Town, they opened small shops specialising in readily saleable commodities as old clothes, cheap jewellery, pens, pencils, umbrellas, optical lenses and often spurious medicines. With immense energy and versatility, these pioneer Jewish traders found a niche in Manchester's growing market for their cheap goods and for services including pawnbroking, and laid the basis of a Jewish communal life. By the time of Nathan's arrival, there existed at least the rudiments of a coherent and religiously observant community.

Denization

Jews born in England, while not receiving the same privileges of citizenship as Englishmen, were protected under English law, and were no worse off than Catholics or Dissenters. Foreign born Jews, however, in certain conditions, could, after 1740, place themselves without the taking of the Sacrament in the same category by becoming denizens, the then equivalent of naturalization. This was an expensive affair, and for this purpose several persons usually clubbed together.

Denization dates back to the 13th century, by which an alien (foreigner), through letters patent, became a denizen, thereby obtaining certain rights otherwise normally enjoyed only by the King's (or Queen's) subjects, including the right to hold land. The denizen was neither a subject (with citizenship or nationality) nor an alien, but had a status akin to permanent residency today. While one could become a subject via naturalisation, this required a private act of Parliament; in contrast, denization was cheaper, quicker, and simpler. Denization fell into obsolescence when the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act 1914 simplified the naturalisation process. Denization occurred by a grant of letters patent, an exercise of the royal prerogative. Denizens paid a fee and took an oath of allegiance to the crown. The status of denizen allowed a foreigner to purchase property, although a denizen could not inherit property. Sir William Blackstone wrote "A denizen is a kind of middle state, between an alien and a natural-born subject, and partakes of both." The denizen had limited political rights: he could vote, but could not be a member of parliament or hold any civil or military office of trust. The last denization was granted to the Dutch painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema in 1873.

Nathan Mayer Rothschild’s application for denization

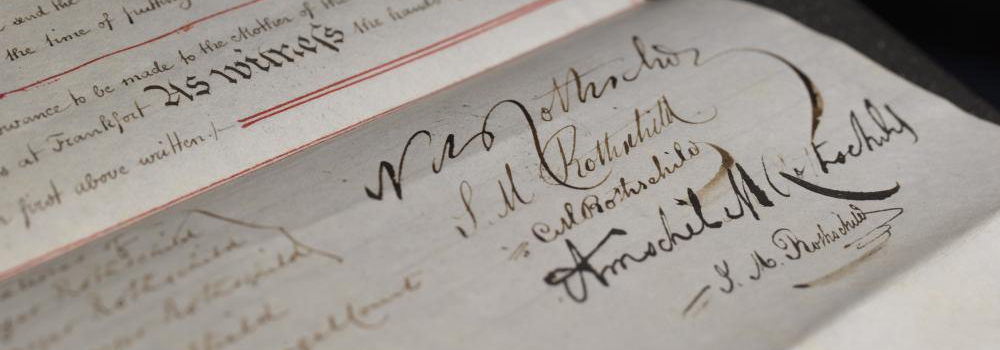

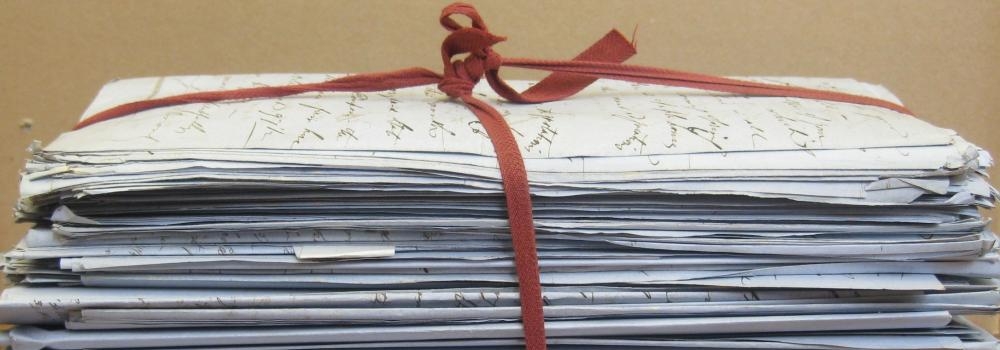

While the Napoleonic wars raged in Europe, Nathan was anxious to secure residency rights in England, and wrote to business contacts for advice on the best method. In his signed application (now in The National Archives) dated 16 May 1804, Nathan states that he “has resided for three years last Past in that Part of the Kingdom of Great Britain called England and being an alien born is desirous to settle in the said Kingdom ... to which he has removed his effects”. Nathan's cautious statement of the length of time he had been in the country probably reflects the period of transition during which he was still travelling to and from Frankfurt. Further evidence of Nathan’s application can be found in the 'Aliens entry book', also in The National Archives.

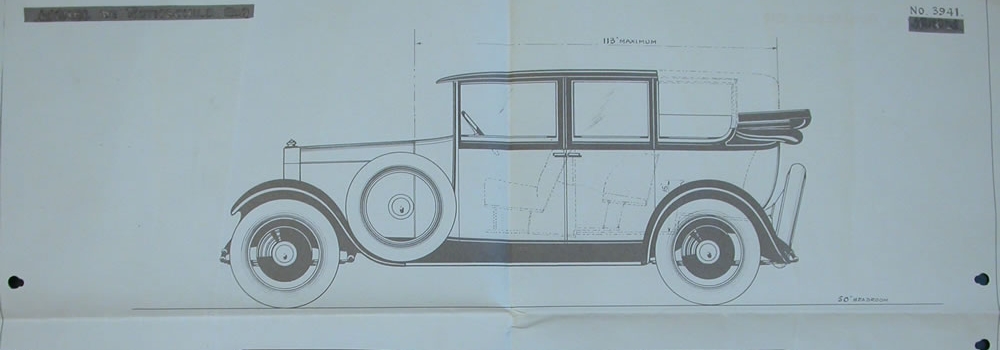

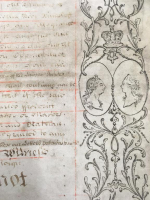

Nathan's denization was granted by the Crown, on payment of a fee, in the form of Royal Letters Patent. The Letters Patent of Denization (in the collection of The Rothschild Archive) were granted on 20 June 1804. The document records his name at the end of a list of seven individuals: Gottlieb Wolf, from Wurtemburg, Simon Levin, from Konisburg, Roderick Willink, from Altona, Natan Ben Rindskopf [a cousin of Nathan’s], from Frankfurt, Charles Frederick Straubert [all from London], Solomon Oppenheimer, from Prussia, and Nathan Mayer Rothschild, from Frankfurt, [both from Manchester].

Nathan’s foresight in acquiring denizenship was to provide a firm foundation to put him in a position to marry well, to provide security for his yet unborn children, and upon which to build his business in Manchester and then in London.

RAL 000/306/1