We take this opportunity to reflect upon how those who came before us took care to ensure that the stories of their times would be remembered and passed to generations as yet unborn, and how we will record the experiences of our times.

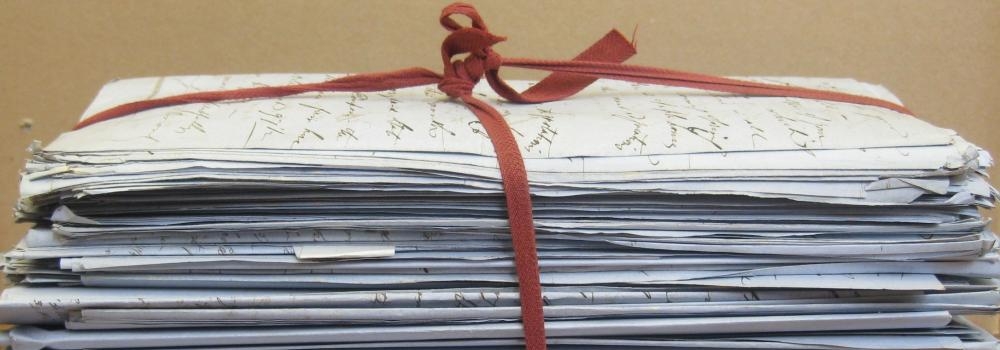

In 2002, The Rothschild Archive received an important consignment of papers, a collection of historic records of the Viennese Rothschilds. After the Anschluss in 1938, archives were forcibly taken from the Viennese Rothschild family; the family were scattered to France, England and the United States, stripped of their homes, their business taken over. ‘Twice looted’, the papers taken were eventually seized by the Soviet Red Army and found their way into the Moscow State Archive. It was not until 2001, following lengthy negotiations between the Rothschild family and the Russian government, that the papers were released to the late Mrs Bettina Looram (1924-2012), heir of the Viennese Rothschild family; Mrs Looram then transferred the records to the custody of The Rothschild Archive.

The papers primarily relate to the Vienna banking house, S M von Rothschild, founded by Salomon Mayer von Rothschild (1774-1855), but also contain early material relating to the Frankfurt business of Salomon’s father, Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744-1812). The return of these papers gives a glimpse of what was almost certainly the first attempt to create a ‘Rothschild Archive’ 176 years ago.

Salomon’s Archive

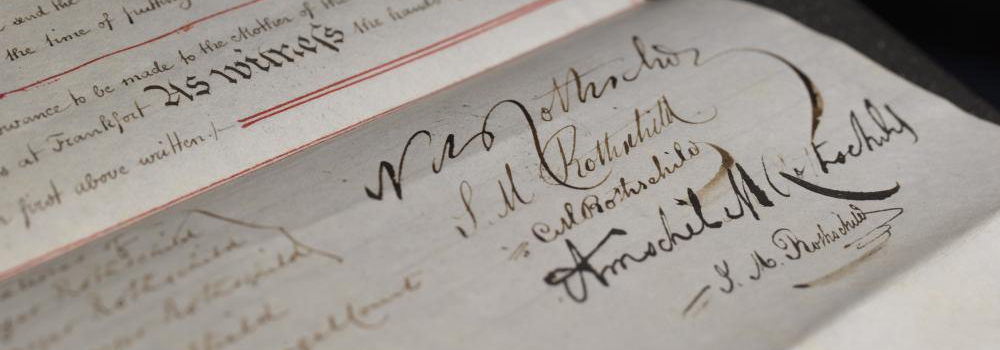

“The records in this register, together with the register itself, are, for all time, to be held in the safekeeping of my dear son, Baron Anselm Salomon von Rothschild, and thereafter in the archives of the entailed estate of his successors, in perpetual remembrance by these descendants of their ancestors. This is the firm and certain intent of the undersigned Baron Salomon Mayer von Rothschild, 20 October 1844.”

This inscription, in Salomon’s own hand, will be found within the covers of a small brown leather-bound volume amongst the papers returned from Moscow. On its cover, tooled in gold, the title ‘Familien Archiv Register’ defines the aspiration which led to this first attempt to bring together key documents in the history of the Rothschild family. It is perhaps not surprising that it should have been Salomon who took an interest in recording his family’s achievements in this way, for amongst the family, his was the most sharply honed sense of history, his letters to his brothers recalling their childhood in the Jewish ghetto in Frankfurt, and his 70th birthday in 1844 would also have focused his mind as to the legacy he would leave behind.

Altogether 67 documents were gathered together by Salomon and classified alphabetically in the Register; 49 have so far been identified as having survived their enforced journey to Moscow. The Register gives no real sense of Salomon’s selection criteria, or where he found the materials for his Archive (the oldest item in Salomon’s Archive was already 75 years old when he created his collection). Did he search through his homes and the bank vaults in Frankfurt and Vienna looking for ‘old’ things, or was the family already accustomed to preserving documents and artefacts?

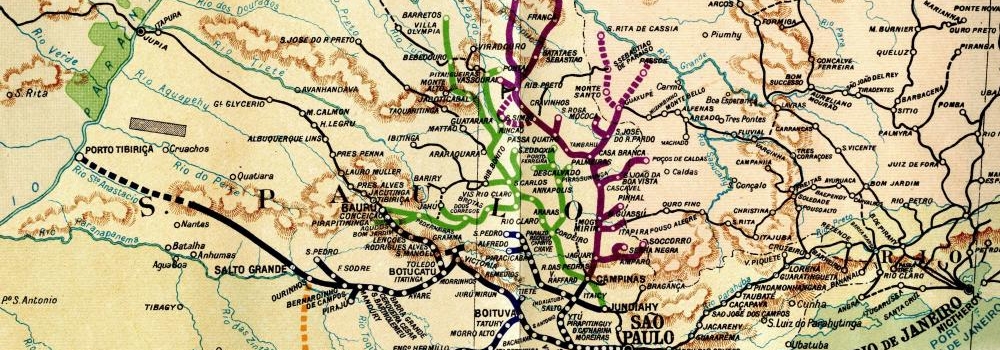

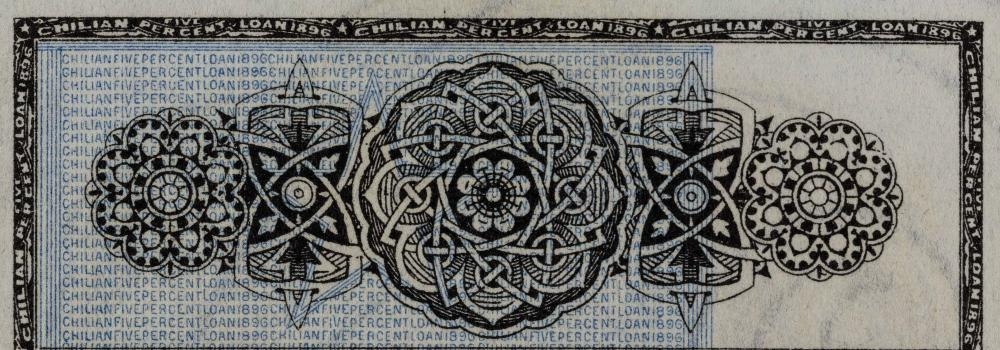

Whether or not his aim was to represent specific aspects of his family’s achievement, the documents in the Archive cover a number of ‘themes’. First among these is the life of his father, Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744-1812). In their letters the brothers frequently invoke their father’s memory, reminding one another of his business principles; he had made clear to them that he expected them to work together in harmony to create a business that would endure. The earliest title acquired by the Rothschild family – the award of the status of Court Agent (Hoffaktor) of Hesse, granted to Mayer Amschel Rothschild in 1769 marks the very beginning of the Rothschild family’s rise as financial advisors in Europe. Its survival in these papers provides us with one of the family’s earliest known business documents.

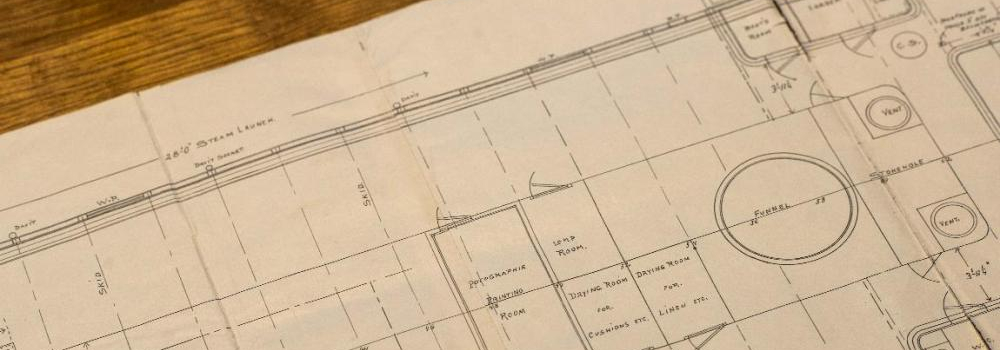

Other documents relate to property. The acquisition of property had a deeper significance for the Rothschild family than for their non-Jewish contemporaries: as Jews, they had long been debarred from the purchase of real estate, except in designated areas. Two items in the Archive relate to property in Frankfurt: one to the acquisition of land on Fahrgassein 1809 on which to build a new banking house and the other a contract for the construction of a synagogue in 1843. Finally, there is a collection documents concerning the family’s pride in the effect their own achievements had on the rest of their community, including documents conveying titles from Austria, Hesse, Prussia, France, Denmark, Russia, Naples and Belgium upon the brothers. Other papers attest to Rothschild family philanthropy, and a collection of addresses and letters of thanks reflect to the celebrations in 1843 of Salomon’s honorary citizenship and of his 70th birthday in 1844.

Salmon made clear his intention that the remembrance of the past and the keeping of archives was an important duty to be passed on, indicating in his preface to the Register that he wanted the Archive to pass to the care of his son, Anselm (1803-1874). Further documentation in the collection suggests that Anselm respected this wish, and indeed added to the collection.

Recording our own time

Throughout history, and often during challenging and dangerous times, people have sought to record their thoughts, experiences and lives. Not necessarily to support some collective memory-making exercise but just to make sense of the extraordinary times in which they are living. Think of Samuel Pepys (1633-1703), whose diary from 1660 to 1669 is one of the most important primary sources for the English Restoration period, providing eyewitness accounts of the Great Plague of London and the Great Fire of London. Or more heart-breakingly, the diary kept by Anne Frank (1929-1945), isolated in her Dutch attic, in which she documents her life in hiding from 1942 to 1944 during the German occupation of the Netherlands in the Second World War. Again, during the war, in the UK, ‘Mass-Observation’ was created to record everyday life in Britain through a panel of around 500 untrained volunteer observers who either maintained diaries or replied to questionnaires.

An appreciation of these sources prompted staff of the Archive to consider how we are recording the extraordinary times of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic. We have invited Rothschild & Co colleagues to send us their own personal archives, and we are working with Rothschild & Co to capture the corporate response to the crisis.

RAL 000/1059 (637-1-314)